Early Life and the 1973 Shootout

Born Joanne Deborah Chesimard in Harlem, Assata Shakur grew up amid the civil‑rights turbulence of the 1960s. By the early 1970s she had drifted into radical politics, joining the Black Liberation Army (BLA), a group that believed armed struggle was the only way to end racism. Between 1971 and 1973 she faced several arrests for robbery and kidnapping, but the episode that made her a household name happened on the New Jersey Turnpike.

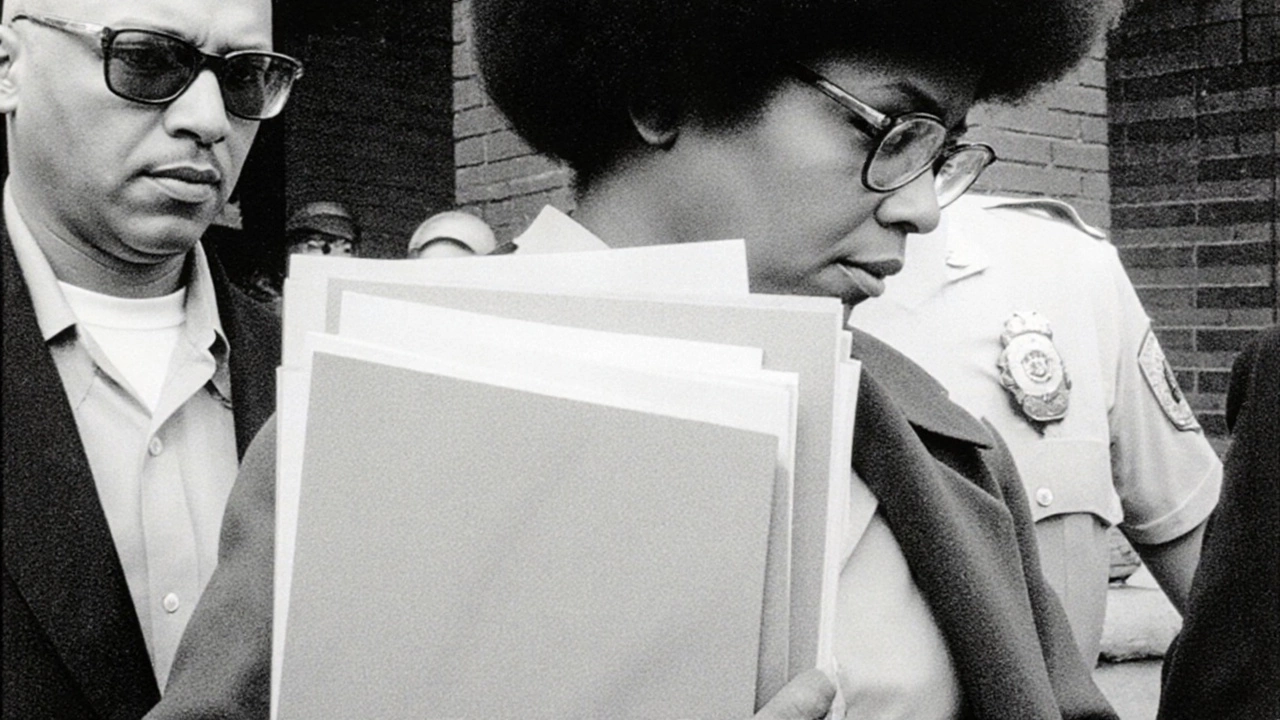

On May 2, 1973, a convoy of New Jersey State Troopers tried to stop a car suspected of carrying weapons. The stop turned into a deadly gunfight. Trooper Werner Foerster and a BLA member, Zayd Malik Shakur, were killed; another trooper, James Harper, was wounded. Joanne Chesimard, who would later adopt the name Assata Shakur, was also shot in the arm, leaving it partially paralyzed. Her defense later argued that the injury made it impossible for her to fire the weapon that killed Foerster.

Six months after the shootout, a series of trials began. She was tried on nine counts, ranging from murder to armed robbery. The jury acquitted her of three charges, dismissed three others, but convicted her on the murder of Trooper Foerster and seven related felonies. The conviction carried a life sentence at Clinton Correctional Facility for Women in New Jersey.

Escape, Asylum, and the Long‑term Fugitive Saga

Prison life was harsh, but the real storm came in November 1979. With help from the BLA and the May 19 Communist Organization, Shakur executed a daring breakout: she slipped through a window, scaled a fence, and was smuggled out in a laundry cart. She fled to New York, then caught a flight to Cuba with a forged passport.

Cuba, embroiled in a Cold War standoff with Washington, granted her political asylum in 1984, calling her a victim of American racism. Over the years she appeared in several Cuban‑produced interviews, reaffirming her revolutionary beliefs and condemning U.S. policies. The American government never stopped trying to bring her back. Extradition requests were rebuffed, and each new administration added its own spin on the case.

In 2013 the FBI added her birth name to the Most Wanted Terrorists list, making Shakur the first woman ever to earn that grim distinction. The listing sparked debate: some saw her as a terrorist, others as a political refugee. The move intensified the already frosty U.S.–Cuba relationship, especially as both countries grappled with the legacy of Cold War-era disputes.

Even as the world changed, Shakur kept a low profile in Havana. She taught English, wrote essays, and occasionally addressed crowds about black liberation and anti‑imperialism. Her health began to decline in the early 2020s, and on September 25, 2025, the Cuban Ministry of Foreign Affairs announced her death at age 78, citing age‑related illnesses.

Assata Shakur’s story remains a flashpoint for discussions about race, political asylum, and the limits of law enforcement. From a New Jersey prison to a Cuban exile, her life spanned the most contentious chapters of late‑20th‑century American activism. Her death marks the end of one of the longest‑running fugitive pursuits in U.S. history, but the debates she ignited are far from settled.